The phone call that changed my life

The Sunday Times Review, Turning Point, May 30, 1999

By Salone Mehta

“Don't get me wrong, I'm not being cynical,” clarifies Mahesh Bhatt often enough to indicate that this is a repeated allegation he faces for his stark honesty. What gives this man the courage to break the mould, “not to be a party to his own myth-making…not to confuse his clothes for his skin…and not be streamlined” into conventional thought processes?

“I'm pathologically opposed to authority,” Bhatt explains, trashing schools and educational institutions as “concentration camps where they cut and prune you, after talking of originality.” What has made Bhatt the filmmaker that he is? Was there one defining moment that changed his life?

Becoming a filmmaker was not a turning point for him, but a natural calling, born as he was into a family of filmmakers. “The need to make money to help my mother who was rattling with problems every day, was what propelled me into cinema. Self-expression was a luxury that a middle class boy, who used to sell air purifiers at petrol pumps, could ill afford,” he explains. He was a storyteller all right, drawing from his own story and the story of others, and cinema was to be his tool.

“Blood-letting” is what filmmaking is for him, the source of his creativity, being his own wounds. “Sorrow is the clue. Sorrow is the human heritage on which the entire art and culture industry is built.”

According to him, even Christianity is based on a story of suffering and redemption. “In school the story of Christ fascinated me. A man in revolt with his times, his crucifixion, his obsession with his mother which I could understand because of my own relationship with my mother, and the theory of resurrection.” Bhatt, the eternal storyteller, learnt the important need of “the happy ending.” Good Friday was necessarily followed by Easter, the resurrection being the happy ending, that ensured believers and followers.

Bhatt then rewinds to 1978, the watershed year that was to largely determine the man that he is today. That year was to free him of an addiction, the pernicious hold of Bhagwan Rajneesh. “Looking at one's past is like looking at things from the wrong end of the telescope. It makes everything look distant and small,” he says.

“Those were the days of living dangerously,” he recalls, “of reading Jonathan Livingston Seagull, listening to John Lennon and taking LSD. I was meditating that morning when the phone rang. As I walked to pick up the phone, little did I know that this call would change my entire life.”

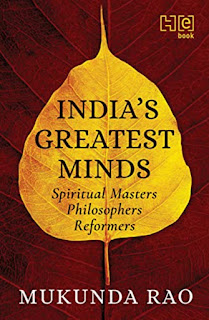

The phone call was to result in a meeting (thanks to Pratap Karvat) with another Guru, UG Krishnamurthy, whose philosophy changed the course of his thinking and belief. Reading out from the biography that he has written about UG Krishnamurthy, Bhatt continues about his first meeting with UG. “I felt scorched. Accidentally I had touched a live wire. Walked into a field of mines. His words jolted me out of the spiritual coma I had sunk into.”

Bhagwan Rajneesh had lulled him into a sense of well-being, but of a short-lived nature. The Bhagwan had become a crutch. He was constantly back at the ashram for more, pinned to “a dog collar, which kept him on a leash for almost three years.”

“It was a paradox. My quest for freedom was transformed into a trap, a prison from which I blurted out concepts of liberty and independence. My encounter with UG had left me traumatised. Deep within me a wound festered. You can run but you cannot hide. You can lie to the whole world but not to yourself. I knew my days with Rajneesh were numbered.”

UG's words gave him strength and courage, courage when he said, “A guru is one who tells you to throw away all crutches. He would ask you to walk if you fall.”

Bhatt committed a “sacrilege” by physically flushing the mala Rajneesh had given him down the loo. Even though the shift in belief brought on threats of destruction by Bhagwan Rajneesh, Bhatt said to himself, “Who is afraid of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh? Get up on your own two feet, no matter how shaky they are and walk.” Once he obeyed his own command there was no turning back.

Bhatt became a man freed of his own phobias. He had always been scared of the dark. And UG freed him of that by saying, “So, what's wrong with your being scared of the dark?” Bhatt makes his point by saying, “I am still scared of the dark, but I am not scared that I am scared of the dark.”

UG to him is still his hero, after decades of association. He has given Bhatt the courage and conviction to live with daring honesty. His mantra is, “Achieve success by fair means if possible, foul means if necessary.”